Psychobiography

In Switzerland: Childrearing Aimed at National Consent

by Marc-André Cotton—Int. Psychohistorical Association

This article was published in the peer-reviewd publication The Journal of Psychohistory, Volume 36, No 2, Fall 2008. Clic here to read the original French version article.

Abstract: The “Swiss consent” is the political consequence of severe childrearing demands, which parents inflict on the child’s spontaneous consciousness. The ensuing sufferings are the origin of a recurring social ill being that reproduces in the Swiss political life, particularly in the growing stream of nationalism and xenophobia.

Switzerland cannot be considered as a “nation” in the usual significance of the word. Made of four different linguistic areas and of twenty-three cantons united in the Swiss Confederacy, it is shaped with local traditions to which its inhabitants remain fiercely loyal. Its political situation is a consequence of the ability of its members—weakened by internal quarrels during many centuries—to compromise for their survival with a central power called “federal” all the while sparing the sovereignty of the cantons. Nevertheless, one of our essayists, a fervent supporter of the Swiss political model, wrote: “[T]he name of Switzerland indicates a particular way of living together, a particular structure in public relations, the idea […] of a society of the free men[1]…” Such a mythical construct is meant to disguise the reality of historical and personal sufferings that Swiss people restage collectively, at the expense of the new generation. It comes along with a profound faithfulness that a spirit of goodwill and personal renouncement is the essence of our common wealth.

Swiss relational distress

Such a worship of compromise, which is almost religious in Switzerland, is a defense mechanism rooted in the history of Swiss families. Meant to repress long hidden sufferings, it reveals precisely how inadequate interpersonal relations can be and thus comes with a considerable social cost. According to a 2003 study by the Federal Board of Statistics for instance, 44 percent of the working population “admit that they experience intense nervous strain on their working place” rousing important health disorders. Another survey shows that the Swiss suffer from the highest professional stress in Europe and some experts also link this to “a growing lack of sexual desire in the Swiss population.” To protect family life from the pervasive consequence of professional stress, the Economic Secretary of State has printed a booklet that notably exhorts employees not to think about their job once they get home, “visualizing a stop sign” or “concentrating on one’s breath” to avoid unwanted preoccupations[2]. Such an advice cannot put an end to the Swiss malaise however, because the professional environment is revealing of schemes of behavior that prevail in social life, particularly the ones children experience when they face severe childrearing demands by their parents and teachers. What we generally call “stress” is basically a reaction to the childrearing attitude parents oppose to the spontaneous expressiveness of the child. The restaging of such interactions in the context of working pressure generates symptoms such as anxiety, lack of self-esteem or feelings of helplessness. Unable to “say no” to the hold of those inner voices, the victim of “stress” becomes his own torturer and that of others too. Nervous breakdowns, physical symptoms and job burnouts are manifestations of such problematics.

Switzerland also shows among the highest rates of suicide in the world. According to a study requested by the Federal Public Health Office (OFSP) after a deputy’s interpellation in the Parliament, the Swiss average suicide rate was 19.1 out of a hundred thousand in 2000, the world suicide rate averaging 14.5 and the United States rate being 10.6 out of a hundred thousand that same year[3]. The study observes that, in Switzerland, deaths by suicide outnumber the total of deaths by car accidents, AIDS related diseases and drugs. It states: “Suicide and suicide attempts are public health issues that cannot be restricted to individuals. Their prevention is a necessity for our society as a whole[4].” The report emphasizes that the person’s background and psychic vulnerability play a major role. Indeed, persons who have been suffering from depression, diagnosed mental illness or drug addiction commit 90 percent of suicides, suggesting that emotional distress is particularly prominent in this country. It is therefore necessary to acknowledge that such symptoms find a common source in the adults’ compulsion to educate children in order that they fit into the collective project, thereby reenacting the denial of their human nature.

A parental project

The present essay aims at defining what characterizes the Swiss childrearing. It started years ago as I began to realize, through the process of psychotherapy, that my own upbringing hadn’t been as likable as my parents wanted me to believe and to acknowledge long denied sufferings from childhood. I found the idea of a “project” at the very heart of my conception. In my parents’ eyes, I wasn’t a conscious human being but a part of a project because that’s the way they had envisioned their life as a couple. There wasn’t scarcely any space left for the vital impulse of a child because such spontaneity was a threat to the project they had conceived: as children, we weren’t supposed to cry or to express anger for instance. I realized that the Swiss proneness to conformity is linked to the contempt parents unconsciously inflict on their youngsters’ emotional needs from the very start, as they comply with this collective aspiration for consent. At some point, I recognized that the newborn cries of despair I was expressing during therapy sessions were evidence of severe deficiency in mothering, of which my mother was responsible despite her efforts to deny such reality. Mastering her child’s vitality was a priority: she gave me scarce physical contact, breastfed on fixed hours and was obsessed with toilet training. I later realized that my father had played his part too. As he refused to re-experience old sufferings that emerged with the prospect of becoming daddy, he put his professional career in rivalry with his children’s emotional needs, pressing his spouse to turn away from them to support a personal challenge of which he was the focusing point.

In Switzerland, rituals of all kinds rule childhood. As far as I am concerned, it was daily morning showers, domestic chores to get used to family service, prayers before meals and bedtime, religious services and family reunions, etc. Emotional abandonment and strict parental obedience were the law. I was spanked as a baby, was given cold showers as a toddler and, if rods or belts were not used, I recall being threatened with a carpet beater. As my parents required, I complied and repressed the terror of being “incarcerated”, of living in a detention center where everything was anticipated, organized and planned for. Even sexuality was addressed through a technical description of gender anatomy lacking the emotions they unconsciously related to insanity. Submitting to their influence, I came to idealize my parents and the world around me. Because no one was listening to my despair, I ended up inflicting myself the same decrees by which they were manipulating: I can be useful and with pride; I must help mommy; I would like a reward…

Childrearing and frustration

The way the members of a given social group consider children, even before they are conceived, has a dramatic consequence on the ways they will be brought up later on. It is conditioned by preconceptions resulting from the routine control that adults exert on their own repressed sufferings. As a matter of fact, without their acknowledgement of the psychological circumstances in which they themselves grew up, parents tend to seize their offspring in the reenactment of socially and family inherited schemes of behavior, thereby perpetuating the patterns of denial they were subjected to. Many renowned experts for instance, relayed by Swiss mainstream media, stress the importance of “frustration” in childrearing. These authors reach a captive audience among most adults because grown-ups don’t realize how much their emotional life has been ruined by their own parents’ inability to be respectful of their inner self and to fulfill their intrinsic needs as children. The compulsion to “frustrate” their offspring in a similar fashion is a way to actively repress these hidden sufferings.

A few years back, a columnist from Geneva wrote on that account: “Children whom are never told a ‘no’ always end up bullying their parents, turning their mother into a ‘mat mommy’ they can always wipe their feet on and pour out whatever they want. And the later you wait, the harder it gets.” Here the author doesn’t make any difference between refusing to fulfill essential needs, such as breast-feeding, and withholding an object of gratification for instance, which is meant to compensate for the frustration of early essential needs. In an article dedicated to “parental dismissal”, he explains a various number of adolescent symptoms as the outcome of a lack of “frustration” in childrearing: “feeding disorders, depressions and suicide attempts, addictions and defiant misbehavior, and also anxieties, feelings of inner vacuity, inferiority or inhibition[5]…” With such state of mind, adults refrain from any question that would challenge the core relationship they establish with children and the attitude their own parents had with them (fig. 1).

Fig. 1 : Adults project onto the child the patterns of behavior their own parents showed towards them, thus justifying to reproduce on him/her the violence and contempt they suffered themselves. —“Woman! Give me a steak to put on my saddle. It’ll make it tender.” “I only have ground beef, dear.” “It will do!”— (Construire No 5, 01/28/03)

Yesterday and today

Up to the end of World War II, living conditions were austere in the Swiss valleys and countryside. A clannish state of mind prevailed in rural and mountain communities. Families often numbered up to ten or twelve children and endured the dominion of an irascible patriarch—often a heavy drinker and violent man. Subjected to all sorts of tasks, children were promptly submitted to family economics and those whose native land could not nourish had to leave for the cities where they became factory workers. The girls were particularly despised. Those who were excluded from marriage were sent to work as housemaids at the age of fifteen, and sometimes younger. Others remained single to serve their aging parents, like this woman from Évolène, in the Valais mountains, whose mother claimed: “We breed boys for life and girls to be at our service[6].”

Who can tell the sum of humiliations, of frustrations and resignations held captive in the secrecy of these individual destinies? Such painful feelings are part of a repressed legacy inflicted to the Swiss offspring through preconceived ideas always victimizing children first. Despised girls become mothers themselves and reprimand their progeny as being “despotic” or willing to turn them into “mat-mommies”, without questioning the true parental despotism they endured in their youth. For similar reasons, Swiss men claim the right to “frustrate” their children to avoid the dreadful feelings they themselves repressed when they were deprived of early maternal love. Parents thus construct a childrearing discourse aimed at containing and directing their child’s vitality to refrain the emotions they live in contact with his natural spontaneity. Here again, the media and eminent experts go on with old childrearing recipes: “Be careful not to turn him into a spoiled child. There must be a certain amount of frustration in childrearing[7].” Such comments show how aggressive the projections inflicted on the child’s sensitivity can be, as they indubitably come from adults who themselves were “spoiled” by the frustration of their natural needs as children.

A wide media coverage

In an article on childrearing written for Construire, a free weekly distributed by Swiss leading Migros department stores to more than 500,000 families, a columnist laments: “Every time you get into a shop, it’s an absolute zoo! Your kid begs for his share of sweets and gimmicks. If you refuse, he gets mad at you and makes you feel shameful in front of everybody’s eyes. Intolerable[8]!” Instead of inviting parents to question their modes of consumption that is, the neurotic ways they use in order to cope with their daily frustration, thereby suggesting how a child’s behavior in fact mirrors his parents’ reactions, the author rather calls him a “brawling brat” and suspects he’s “manipulating”. Committed to the principles he was himself brought up to, he sticks to this sole motto: “Resist!” Then follows a list of parental “guidelines” that shows how adults proceed to manage the vitality of the child, all the while suggesting—in order to maintain a good image of themselves—he is manipulating them.

First of all, one must clearly justify the idea that children are driven by untamed impulses: “Try to make him understand he cannot simply possess all that he sees.” This statement seems reasonable but hides a profound disdain for the child’s spontaneity and a ferocity that will surely burst if the youngster doesn’t comply. More explicitly, the author then suggests: “If your little devil shows the slightest sign of grievance, stand firm and, if he seizes a toy, order that he puts it in place immediately.” The role ascribed to parents is now more clearly repressive and the columnist himself resorts to imperious expressions so as to oppose any objection. Quoting yet another expert, he finally justifies an attitude of stubborn dismissal on the parents’ part—“The child must realize that, whatever he does, you won’t change your mind.” And concludes by advocating common deceptions by adults: “Isn’t diplomacy one of Switzerland’s special talents?”

The “hygienic reform”

Such a collective urge to frustrate and educate notably relates to the combined effort of the ruling class, since the late Nineteenth Century, to condition the populace to submit to the requirements of the nation’s industrialization. At that time, the ravages of tuberculosis or alcoholism, unhealthy housing or child mortality were all symptoms of a deeper misery resulting from routine denials inflicted on the consciousness of all human beings. But as the Swiss authorities were unwilling to confront such problematic, they rather promoted public hygiene and moralization of the working class. In doing so, the wealthy were reaffirming the mental projections of “dirt” they routinely cast on common people instead of simply meeting basic needs for security and bonding that allow young mothers to naturally satisfy their newborns and youngsters.

Under the pressure of what would be later known as the “hygienic reform”, life at home was profoundly remodeled. In the name of physical and moral health, the “clean” and the “dirty” became the new boundaries separating the permitted from the rejected thereby revealing the pure out of the impure. Disconnected from the repressed origins of all collective sufferings, the authorities resolved to enroll the working class—women in particular—in the process of “social improvement” and economic development sought by the wealthiest and most influential intellectuals. That is when the Leagues of Public Utility were created to strongly encourage domestic hygiene as a national priority[9]. In the newly created Household Academies intended for working class girls (fig. 2), mothers-to-be were instructed in the latest “science of domestic management”, including practices considered from now on as being indispensable to modern housewives and gestures to perform in the nurturing of infants. Such a teaching was supposed to instill “the love for domestic duties, as well as the practice of enlightened commitment[10].”. Having endured contempt for so long, women found in these rules of home maintenance a compensation for the agony of still not being recognized, listened to and loved. As a result, they seized their children as objects of this new urge to clean everything.

Fig. 2 : In Household Academies, mothers-to-be learned standardized gestures they would later exercise compulsively in the care of their children. (Sewing class at Ecole Valentin, Lausanne, around 1923)

Mothering and mental projections

In the 1920s, the methods in obstetrics and infant care were strictly oriented towards separating children from their mother at birth, as a measure of social hygiene and education. At the time, a very popular book, written by German lady doctor Johanna Haarer, recommended that the newborn baby be placed in a separate room for 24 hours, alone if possible, after being bathed, clothed and medically examined: “Separation between mother and child offers extraordinary benefits in childrearing for the latter. Later on, we shall mostly stress the fact that the training of the child must begin at birth[11].” As the labor process was medicalized and industrialized, such recommendations became routine. In a more recent edition of the same book, one can read: “In modern maternity hospitals, [the newborn] is immediately taken from the mother to be examined by a specialist in infantile diseases[12].” Yet, when the birth process is not disturbed, we very well know that mother and child are naturally bound towards each other. These early instants determine the development of their future relation. For instance, if the baby is separated from his mother during this sensitive stage, the latter will have trouble renewing the lost intimacy and responding to her baby’s needs, because—in an unconscious effort to spare the responsibility of the medical team—she’ll tend to make her child accountable for the bitterness of having been deprived of those precious moments. Furthermore, such a rupture hardens the mother and conditions the child to submit to various forms of social control.

Because they do not question most people’s standard of living, the allegations of the new hygienic science strengthen the common belief that babies—just like women—are “basically dirty” and that the infants’ “salvation” lies in their mother’s will to cleanse them zealously, as if they were yet another household chore: “In the early months of childhood, cleanliness is of vital importance! The health and good development of the child mainly depend on the way you will carry out this duty. You know that pathogenic germs exist everywhere in our environment. For instance, the emissions that flow from your internal organs after birth can hold pus, bacillus of diphtheria or other microbes[13]…” Instructions given for infant care thus encourage young mothers, whom natural sensitivity is despised, to use the same domestic principles they learned at the Household Academies with their offspring, which includes the imposition of a very harmful detachment for the sake of hygiene: “Wash your hands every time you take care of your baby!” or else “Use a clean apron, different from the one you wear for your household chores!”

Unbearable dread

When subjected to such demeanor, infants suffer great emotional and interpersonal deficiencies, which will later reappear in the form of compulsive relations with orderliness and cleanliness. Harassed at the moment of their birth and deprived of an indispensable intimacy with their mother, they are prematurely weaned and must swallow unhealthy nutriments frequently causing painful colics. If they show any signs of suffering, their mother will provide at best only standardized and very functional care. Most of the time though, they must cope with isolation and repress the unbearable dread that they might lose all contacts with her, which inevitably implies the fear of dying. As they cannot alter their mother’s refusal to meet their needs, they internalize a failure to relate with her. As growing children, they will tend to make up—by means of compulsive attachments and behaviors—for the empathy, affection and love they were deprived of at the dawn of their life. The training of such compulsive conducts, which are considered as being socially inappropriate, is an integral part of the parental project to commit children to “earn their independence and grow”—thus avoiding any resolution of family problematics.

In a recent article appearing in the column “Your children” of the Swiss weekly Construire, the columnist asks with irony: “What a disaster! Your child has lost its fetishistic and transitional object! How can you help it[14]?” This mocking interrogation reveals that adults often feel contempt when facing specific symptoms of suffering by children. Behind a mask of sentimentalism, the author projects the disgust that his own parents inflicted on his relational needs onto the toddler’s object of gratification: “His beloved and droopy Teddy bear is filthy; it stinks and is falling apart. You’re thus asking yourself—like other parents of happy owners of such dirty fetishes—if you can wash or repair the disgusting thing, or even throw it away for that matter…” The columnist doesn’t recommend that parents ponder the question of why they have such difficulties to wholly meet their child’s needs for intimacy, but instead suggests humiliation and contempt or simply lack of concern.

Children are evil

Such willingness to hold children responsible for interpersonal difficulties that are of the adults yields to the transference of family problematics to the next generation. Indeed, children become the unwilling containers of unresolved sufferings that parents and pedagogues refuse to originate in their own childhood, thus projecting them onto youngsters who will be bound to restage theses repressed experiences later on. Not so long ago, Christian educators felt entitled to beat children by claiming that they were sinful and personifications of evil. In reality, these adults were only restaging the violence of their own parents in order to repress the distress of not having been loved but instead awfully beaten and shamed as children.

A cover of the Swiss weekly L’Hebdo (fig. 3) recently showed the eye-catching picture of a toddler with a devil’s horns and tail, pasted between its genitors, with this allegation: “Why children kill couples.” Inside the magazine, a four-page article detailed the “wedded nightmare” supposedly brought by the arrival of a first child. According to a family therapist, the newborn “is the partners’ worst enemy”. Some academic studies mentioned by the authors claim that the child might drive its parents to breakup and that it is responsible for a degenerating process measured in four “weakening class-marks[15]”. We can assume that the all too real marital problems L’Hebdo is referring to are not a child’s fault but originate instead in the parents’ inability to question their own childrearing so as to be able to fully meet their newborn’s natural needs. Unwilling to do so, they tend to view the needing child as a demanding parental figure—the commonly named “domestic tyrant”—whom they will experience as victims. Such state of mind will bring about the restaging of comparable circumstances in which their own needs were despised when they themselves were children.

Fig. 3 : Adults tend to hold their child responsible for their own problems because the child’s nature is perceived as “demoniac”. — “Why children kill couples. More conflicts, less spare time: progeny causes dissension between parents.” (Front page of Swiss magazine L’Hebdo, November 11, 2004)

Violence in childrearing

As toddlers grow up, the adults’ inability to understand their needs and to fulfill them generates feelings of helplessness, which often explode with anger or aggressiveness. Although such behaviors signify juvenile liveliness, they are condemned as being potentially destructive and are thus disciplined. A pedopsychiatrist explains: “The parents’ duty consists in encouraging the integration of the naturally violent instinct of the child[16].” Such a discourse strengthens the outrageous preconceptions that adults cast on the child’s nature, thus forbidding any question about the patterns of interrelationship they impose. In the same article, we also find: “Rogue of the town square, scourge of the playgrounds, Attila [sic!], age 9, loves to knock and show he’s a big chief. The other young rascals fear him […]. The parents of the little brat are worried by such circumstances. And they ask themselves why their lad cannot control his aggressive instincts[17]…” Recourse to violence in childrearing is then strongly suggested—if not openly encouraged—to bring the conflict to an end: “Corporal punishment must be proscribed, the columnist asserts. But there are times when a slap or a good spanking conveys more warmth and contact than endless arguments[18].”

As a group, the Swiss community is still convinced that violence in childrearing is reasonably grounded, given that the magistrates of the Federal Court—the highest legal authority of the country—have recently admitted that parents have a limited right to smack their children. In July 2003, the Supreme Court judges said parents and other persons acting in a parental capacity might use corporal punishment “following inappropriate behavior and with the aim of educating the child”, only repeated punishment is reprehensible[19]. Predictably, the lack of unequivocal denunciation of any violence towards children by public officials and of a clear comprehension of the psychological mechanisms supporting such violence give way to its reproduction. According to a study published by the University of Fribourg (Switzerland) in 2004, most parents resort to corporal punishment in case of “disobedience, screaming, inappropriate eating manners or even boldness”, in particular against their youngest kids. This statistical survey, funded by the Federal Board of Social Insurances, is based on a representative sample of 1,240 Swiss parents from all cantons. Among toddlers of less than thirty months of age, researchers evaluate that about 13,000 are given smacks, 18,000 are pulled by the hair, 35,000 suffer spanking from “occasionally” to “very often” and 1,700 are hit with objects[20].

Brutalized in the cradle

In the late 2001, a dramatic news story brought public attention on violence against young children, eventually arousing some indulgence with regard to parental mistreatment of youngsters and showing how dramatic a stubborn attitude of “consent” can be. On Christmas Eve, a renowned Swiss mountain climber, upset over the cries of his toddler, shook the baby so violently as to provoke an almost instant death. In an article dedicated to “those babies that drive you mad”, L’Hebdo magazine emphasized: “This man depicted as being such a master of himself, never sidestepping a 8,000 meter summit, lost his nerves in front of a seven-month old child[21]”. Quoting some experts, a journalist wondered why crying babies stir up such “desire for murder”, a comment revealing a devastating transference on the child’s behavior. In a psychiatrist’s view indeed, the baby’s cry is meant to hold “a tremendous potential of nuisance” that is accountable for the adult’s wrath and justifies muffling the “tyranny of the new-born baby[22].”. Only a tiny little voice spoke to the contrary, that of an independent midwife who explained: “Babies are amazingly responsive to the emotional strain prevailing around them. They need to discharge such tensions, sometimes for hours, sometimes in place of the family members[23].” In 2003, at the end of the first Shaken Baby Syndrome trial ever held in Switzerland the infanticide father was eventually convicted to a four-month suspended jail sentence.

In the Fribourg survey mentioned earlier, 21.9 percent of parents declared having hit their children within the last six months and 26.4 percent assured never doing so. These figures show a slight improvement since 1990: at that time, 25.7 percent of parents declared having hit their children within the last six months and only 13.2 percent assured never doing so. Thus, it is reasonable to assume that, in the early 1990s, more than 85 percent of Swiss parents had recourse to corporal punishment to discipline their youngsters and that nearly three out of four still do so today. Furthermore, these estimates rely on the outspoken testimony of adults who, on such a controversial issue as child welfare, might be prone to underestimate their usage of physical violence even if confidentiality is guaranteed. Between 1990 and 2004, researchers thereby noted a sharp rise in the use of punishing means such as forbidding or deprivation, as parents tend to discipline their children in ways that are more generally accepted regardless of severe psychological consequences.

Childrearing and psychological violence

Psychological violence often doesn’t make a noise and leaves no physical marks but it can lead children into a hazardous process of self-denial, even self-destruction, or, on the contrary, induce aggressive and antisocial conducts. The Swiss-French Support Groups Association (AGAPA), a network of professional and voluntary counselors who offer psychological assistance to people who were mistreated as children, explains in a leaflet:

“We talk about psychological violence when a child, for instance, is humiliated, ridiculed, denigrated, despised, ostracized or ignored; when it is subjected to mockery or any kind of harassment; when it is taken advantage of or overcharged; when it is influenced, made guilty, submitted to menace, emotional blackmail or threat; when it is left without a reference frame and benchmarks; when it is being involved in conflicts of adults, forced to witness violence; when it is abused to fulfill some other person’s need or interest, etc[24].”

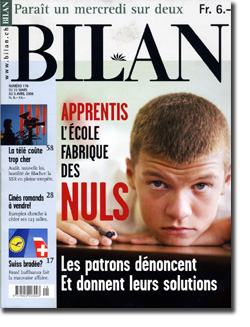

But instead of being publicly condemned for its detrimental consequences on the social fabric, this type of violence is widely encouraged for the sake of a good childrearing and vocational training. For instance, a recent cover of the leading business magazine Bilan, with 130,000 readers in French-speaking Switzerland, features the portrait of a dazed teenager with this humiliating comment: “Schools manufacture DUMMIES” (fig. 4) In an article dedicated to the presumed decline of our trainees’ general education, the editors trot out the same sarcasms that young men and women routinely suffer on the part of their teachers and superiors: “They need a kick in the bud to get started.”; “Young people are lousy and lazy, they only have leisure in mind.” or else “Female clerk trainees remind me of cows watching trains pass by[25]!” Bewildered by their willingness to reproduce on the new generation the same disgrace they were once submitted to, adults do not realize that a lack of incentive or personal initiative, hesitancy or even indifference originate precisely in those routine marks of psychological violence that ruin self-esteem and alter the child’s ability to become a mature and responsible human being.

By contrast, there is a growing consensus of opinion on considering mistreatment of children as a real social issue[26]. Professionals at the Genevan Health Youth Service (SSJ) link this evolution to the adoption, in 1989, of the International Child Rights Convention, although Switzerland ratified this document in 1997[27]. Only in 1999, with the adoption of the new Swiss Constitution mentioning the obligation to protect their integrity, were children finally instated as subjects by law[28]. In 2003, the Genevan Parliament was presented a motion entitled “Mistreatment and violence against newborn babies, children, teenagers and young people, and the resulting social violence[29].”. Since 2004, the Genevan Department of Public Education (DIP) encourages teachers and other professionals to inform on circumstances where children might be at risk[30]. This progress is discernible in the statistical rise of cases of mistreatment reported to the Genevan Health Youth Service since the early 1990s. Between 1989-90 and 2002-03, the total number of reported cases multiplied by thirty, going from 12 to 360 cases. That last year, professionals began to take into account a new category called “children at risk”, arising the total number of endangered children to 1,161, almost a hundred times higher than the cases reported in 1989-90[31]. These figures reveal the strong denial that prevailed only a few years back, even among child welfare professionals, on the subject of child abuse alone. They also bring to light what a formidable resistance adults still oppose to the recognition of all forms of abuse against children, particularly the effects of ordinary violence in childrearing such as routine slaps, punishing, humiliations, emotional withdrawal and other means of psychological harassment.

Fig. 4 : In Switzerland, the psychological violence exerted on children and teenagers is a regular mode of childrearing. (“Trainees: Schools manufacture DUMMIES; Employers inform and giver their solutions.” Front cover of business magazine Bilan No 178, March 23, 2005)

“Positive reinforcement”

Indeed, what is going on in a youngster’s mind? To make up for a profound sense of helplessness and despair, which is the inevitable consequence of the denial they are subjected to, children mould their character to content their parents’ demands. Facing physical and psychological abuse, they adapt with schemes of behavior that are commonly praised around them. In Switzerland, parents most commonly instill in their offspring’s mind the moral values of “community service” and “duty” with a sense of self-sacrifice. In an article on “Daily rules”, published by Genevan newspaper Le Courrier, we can read: “Selfishness, egocentricity and irresponsibility threaten children whom are exempted from household choirs. And no preferential treatment should be granted to male subjects[32].”

How can one submit the child once the parents’ demands have been legitimatized? The newspaper continues: “You must first begin at the earliest age. As young as two, a child must have a sense of usefulness, but only in a way that is adjusted to its young age.” The female author of this article then gives a suitable example of what mothers should do to help children “gain independence”, for instance by entrusting their youngsters with carrying a loaf of bread while shopping. She states: “[The child’s] young brain perfectly understands that, thanks to its mother’s judicious explanations, it has got an important and useful role to play.” But in reality, the child’s proneness is the result of its parent’s obstinacy to manipulate its distress— for which they are in fact responsible—to impose their childrearing schemes, a process that behaviorists call under the euphemism of “positive reinforcement”. As it cannot simply grow in its mother’s love and presence, the toddler is compelled to adapt by compensating its affliction with the parents’ approval as a substitute. According to this stratagem, the adult must at first propose a task that the child can be expected to perform thoroughly. Should it be too simple to achieve, though, the youngster could “get used to be pampered”. Parents must therefore “consider and even consult each other to evaluate as precisely as possible the current capacities of their child. This deliberation must be carried out regularly as the child grows up, because its assistance must be adjusted or increased according to its development[33].”

Social contract

Such a radical conditioning of the child’s vitality enables parents to repress the terror of simply acknowledging the cause of what he or she is manifesting. Bearing this approach in mind, adults try to control their own repressed anxiety—that resurfaces from their childhood—but soon deprive the child of a genuine emotional liveliness in favor of conventional manners, and impose painful adjustments to parental and social schemes of behavior. In an article on learning difficulties that children face at school, the weekly magazine Construire deplores that Raphaël, an eleven-year old schoolboy, has “intellectual capacities well above the average student but average grades scoring under his potential[34].” According to its schoolteachers, the child is “intelligent but sluggish” and finds all sorts of excuses to “avoid lessons and homework”. A psychologist argues that the boy has become “intolerant to frustration” and suggests his parents regain authority: “You ought to reinforce him positively when he makes progress and punish him when he doesn’t work. After all, can we not link the school contract—which is the No 1 contract children must conform to—with pocket money or leisure activities?” He therefore invites parents to “get invested” in the schooling of their offspring, thus reducing their presence to a childrearing attitude striving toward a common goal.

This way of thinking finds a particularly encouraging space in Switzerland because we have been led to think that, in the absence of natural resources, our capacity to value our service sector and “smart brains” constitutes a important factor of national wealth. As a result, it seems crucial to increase children’s “intelligence” to avoid they become an encumbrance for their parents and society as a whole. This social contract is the origin of an endemic social ill being. It justifies the denial of the human consciousness by reducing individuals to a collection of capacities that can be exploited. As adults constantly refuse to recognize that they reenact old patterns of behavior, their children and teenagers feel deeply misunderstood and, in turn, internalize the social conditioning imposed by their parents with punishments and rewards. They don’t realize how they distort their views of themselves and others, as well as of life itself.

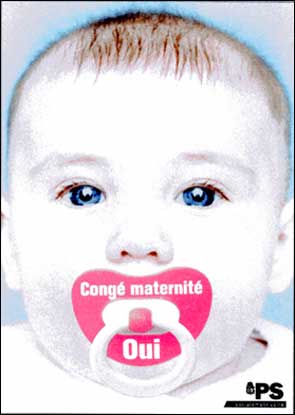

Democratic martyrdom

The political consequence of this unconscious social contract is observable in the field of motherhood and family policies to begin with. Although the right to a paid maternal leave is mentioned in the Swiss Constitution since 1945, mothers awaited a final project for almost sixty years. In 2004, after three proposals were refused in popular voting, the Swiss people finally accepted legal dispositions to fund a fourteen-week maternal leave for female employees only. Deemed as “politically sustainable” by economic circles (Le Temps, 09/27/04), the plan brings up to a hundred million francs in annual savings to the business establishment because salary workers are bound to support half of it. On that account, the Swiss maternal leave cannot be considered a collective acknowledgment of the children’s natural need for maternal bonding. In the view of economic decision-makers, it ought to “still expand the contribution of women to the working force” (L’Hebdo, 08/26/04) in order to guarantee the country’s economic growth and funding of social institutions. From this profit driven vantage point, the maternal leave should encourage reluctant mothers to separate from their baby and go back to work, 41 percent of women currently renouncing to their job after their first pregnancy and 60 percent after the second. In Geneva, free-market advocates have made it clear that the Genevan law comprising a sixteen-week paid leave for mothers should lower to meet the new national standard (Le Courrier, 09/27/04). Such wait-and-see politics, biased by an unconscious sense of revenge, inflict martyrdom to newborn babies who endure unbearable stress and pay the price for the collective short-sightedness (fig. 5).

Fig. 5 : In 2004, Swiss political circles proved disdainful of the child’s natural needs in haggling over new maternal leave project. (“Maternal leave: Yes!” Political poster, September 26, 2004)

Nowadays indeed, numerous studies demonstrate that early emotional deficiencies severely spoil the child’s natural ability to interact with the social environment. According to Sue Gerhardt, psychotherapist and author of Why Love Matters, infants coping with maternal separation will manifest emotional trouble later on: “The strongest research findings are that full-time care during the first and second years is strongly linked to later behavior problems. These are the children who are ‘mean’ to others, who hit and blame other children. They are likely to be less cooperative and more intolerant of frustration[35].” What those children have been deprived of is the presence of a receptive mother, who breastfeeds them freely, holds them in her arms and gazes at them lovingly. Instead of that, they have been committed to service suppliers, to whom they were at best another person’s baby, and had to repress the unbearable distress of loosing, even briefly, their most crucial emotional bonding.

Rampant xenophobia

The traumatic imprint of early emotional abandonment is also noticeable in politics if we consider the relationship Swiss people maintain with foreign-descent residents, a majority of whom have been living in Switzerland for many years or were even born here. After the Second World War, the country began to bring in migrant workers to build its infrastructure and support economic growth. In the 1970s, a larger number of them settled as permanent residents with no access to Swiss citizenship because of expensive and complicated proceedings. In a 2000 report, the European Commission against Racism and Intolerance (ECRI) observed that only about two percent of foreign-descent residents were admitted to Swiss citizenship whereas the majority of them had been living in the country for more than twenty years. The Commission warned that marks of rampant xenophobia and intolerance against non-citizens were not uncommon and even inclined to rise: “Switzerland still doesn’t consider itself a multicultural society whose people can experience a sense of belonging to Switzerland as well as to another cultural or ethnical background[36].” The rejection phenomenon still intensified with the arrival of numerous Albanian-speaking refugees fleeing the Balkan Wars of the 1990s. In 2007, more than 200,000 of them were still living in Switzerland, a population amounting to an average Swiss canton and representing the second foreign-descent community in the country[37].

Controversy over the integration of foreigners has been one of the most permanent issues in Swiss politics for more than a century. On one hand, labor unions and civil society networks campaign to promote a nation of open tolerance, committed to fulfill its duties on an international level. Federal Counselor and socialist Foreign Minister Micheline Calmy-Rey, favored by 73 percent of Swiss people according to a recent poll[38], personifies such humanistic values constitutive of the Swiss public image. On the other hand, a growing number of citizens supports the xenophobic agenda of the Schweizerische Volkspartei (SVP/UDC), or Swiss People’s Party, a nationalist political force based in German-speaking Switzerland whose voting scores have reached historical heights in the last fifteen years. In 2003, there were 55 out of 200 deputies of the Swiss People’s Party at the National Council, the larger Chamber of the Swiss Parliament, against 25 in 1991. In the wake of the last federal elections, in October 2007, the SVP/UDC gained 7 more seats and became the first political force in French-speaking cantons like Vaud or Geneva also. The controversial Federal Counselor and SVP/UDC Interior Minister Christoph Blocher is the charismatic leader of this anti-foreigner movement. Since his election at the Federal Council, end of 2003, he contributed to an undeniable strengthening of the Swiss immigration policy, even suggesting that Swiss citizenship be removed for juvenile delinquents of foreign origin and that they be forced to “leave the country, possibly with their entire family[39].”

Humiliating father

Such provocative statements, although incompatible with basic rules of law guaranteed by the Constitution, draw considerable support from voters who have been, just like Christoph Blocher, bitterly despised as children and are willing to restage in the public sphere the cruelty of their own childrearing. As the seventh child of a family of eleven, the young Christoph soon had to elbow his way in to gain attention from his father Wolfram, a protestant minister who strictly ruled over the family. His brother Gerhard, a minister also, recently portrayed him as “a successful rebel[40].” In an autobiography published in 1999, his sister Judith described the interpersonal climate of the family parsonage, where a humiliating father prevailed in front of whom children must compete to exist:

“The children are aligned very close from one another, but with no physical contact because the meal resembles a parade where everyone stares at the master of the ceremony to obey the given orders. As in a window display, children are pretty, merry and bright, like butterflies pinned by the middle in the purpose of an exhibition. The competence of the crew consists in warding off the questions that the father darts, as if he were conducting a grand manoeuvre[41].”

To the humiliations his eldest brothers and sisters endure in front of his eyes, Christoph favors the company of neighboring peasants whose pragmatism he admires. As a teenager, he attends a school of agriculture against his father’s will, nevertheless studying law at the university of Zurich a few years later and obtaining a doctor’s degree in jurisprudence. In 1983, he gets into debt to buy off the Ems-Chemie Corporation, for an estimated price of 80 million francs, of which he soon becomes Chairman of the board. Twenty years later, Ems-Chemie develops into one of the leading successes of the Swiss stock exchange with a capitalized value of about three billion francs[42]. This business performance draws the admiration of “humble people” who form the traditional electorate of the SVP/UDC of which Christoph Blocher heads the Zurich local section between 1977 and 2003: farmers, artisans, small business contractors and, increasingly, employees and workers of suburban areas. The verbal strokes he darts at his political opponents during his public appearances captivate an already submissive audience, entranced by such restaging of paternal humiliation. Halfway between a Wilhelm Tell and a bogeyman, the figure of Blocher brings an unconscious prospect of revenge on physical and psychological mistreatments his supporters have been victims of in childhood, but that no one ever acknowledged as such.

UN Committee against Torture

The emergence of collective repressed sufferings on the Swiss social scene is singularly visible in SVP/UDC political campaigns against insecurity or foreign immigration. During the 1999 federal election, one SVP/UDC poster likened asylum refugees to criminals breaking into the country through laceration of the Swiss national flag, suggesting they should be guarded against as well as of AIDS[43]. The 2007 SVP/UDC election campaign was illustrated with a picture representing three white sheep kicking a black one out of the Swiss boundaries, with this comment: “For more safety” (fig. 6). In the meantime, notably because of Christoph Blocher’s efforts as Federal Counselor since January 2004, measures against immigration have considerably tightened.

Fig. 6 : The Swiss People’s Party anti-foreigner agenda is a collective restaging of the insecurity endured by children whose natural needs are routinely despised for sake of subordination to group consent. (“For more safety” — SVP/UDC political poster of Federal elections, October 21, 2007)

In September 2006 for instance, 68 percent of Swiss voters approved of a new law on foreigners and a revision of the existing law on asylum, which were both disputed by referendum, authorizing in particular the housing of refugees in camps and accelerating the deportation of illegals. Asylum seekers may now be subjected to police search at home, even without warrant. If their request is turned down, they are deprived of any social help and recalcitrants can be jailed for up to eighteen months. According to Amnesty International, the two laws do not respect basic human rights: “Some measures violate the Geneva Convention on Refugees and the European Convention of Human Rights and infringe on asylum seekers’ rights[44].” As a matter of fact, several refugees have been mistreated on return to their native land, following a refusal recently pronounced by Swiss authorities. In November 2007, on request of a Congolese political opponent, the UN Committee against Torture (CAT) even denounced the attitude of the Federal Office for Migration, which had not examined the position of the requester on the ground that he couldn’t submit valid identity documents on arrival[45].

Foreigners as deprived children

The SVP/UDC political agenda against foreign immigration, supported by a growing fraction of the Swiss electorate, is an unconscious attempt to control the deep confusion adults experience when facing expressions of distress by children. Here, the foreign resident under illegal conditions or simply needing temporary assistance is given the role of this disturbing and intrusive child in the dynamics of collective restaging. Through this defense mechanism, Swiss citizen can repress a sense of deep vulnerability they first experienced as children, as they were deprived of the unconditional love they needed to grow into well-balanced adults. As a result, they tend to replicate on scapegoats the denial they were once subjected to in contempt of their vital needs, of their basic safety and sometimes even of their life.

That’s the reason why a majority of Swiss people transfers on immigrants the fears their own parents directed at their juvenile exuberance, anxious that they refuse to submit to domestic laws or become a burden for the Swiss community. Consequently, residents of foreign origin who manifest difficulties to integrate into the Swiss community because of specific cultural traits or war traumas, like children who do not comply with their parents’ will, are also the most undesirable guests. The SVP/UDC fantasy linking foreigners to criminals particularly resonates with people who have suffered extreme repression of their own exuberance as children. Such citizens consider political measures of restraint against immigrants as “reassuring” because this kind of sanctions triggers the defense mechanism they once developed each time they were confronted to their parents’ rebuff. As they refuse to acknowledge the deep sentiments of despair prompted by this lack of empathy, they give support to political strategies that display such rejection on the social scene.

Christoph Blocher rejected in his turn

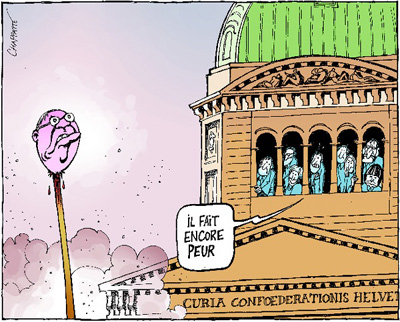

On December 12, 2007, as commentators predicted a facile reelection of the seven-member federal government, the Swiss Parliament refuses to entrust Christoph Blocher for a second mandate as Federal Counselor, choosing instead a more consensual personality of his own party. Having achieved what was expected of him, the leader of the anti-foreigner movement is dismissed with uproar, thereby improving the impaired image of the Swiss democracy in the world. According to daily newspaper Le Temps, this dramatic turn of events, unheard of in the annals of Swiss history, celebrates “the Parliament’s revenge” on a man that political circles consider “a public enemy of democracy” and accuse of undermining the Swiss political model “because he despises Swiss institutions[46].” A political scientist, interview by L’Hebdo magazine, analyses: “It is not a parliamentary coup, but a restoration of conformity. [T]he spirit of concord and corporatism is about to prevail again[47].”. In a press conference given the next day, Blocher confesses relief over being once more “free to speak what [he] thinks” and observes: “It’s not any personal assessment, the people’s will or general interest that prompted this election, only the willingness to repress something[48].”

Fig. 7 : Christoph Blocher’s eviction as Federal Counselor, on December 12, 2007, is a collective restaging penalizing disrespect of the rules of family corporatism. (“He still looks terrifying” — Drawing by Patrick Chappatte, Le Temps, December 13, 2007)

Complexities of the Swiss family problematic are thus once again corroborated. The enfant terrible of Swiss politics, who was given the position of an aggressive whistle blower to give value to our devotion to compromise, is now sacrificed on the altar of national concordance by a prescriptive political elite symbolizing the parental figure (fig. 7). As in his family, beyond fulfillment of the role he was assigned to, Christoph Blocher faces a violent eviction from the government as a punishment penalizing disrespect of the rules of corporatism. It is the replay, at the highest State level, of the denial inflicted on the child’s spontaneous expression who, in desperate need of attention, ends up craving the despotic power imposed by adults. But even brutally pushed aside, the populist speechmaker continues to provoke fear because he could soon direct popular discontent and shake the foundations of our political institutions. As of today, any attempt to adapt these obsolete structures to the necessities of a constantly changing world have bumped into the Swiss compliance to group consent by which we handle our historical and personal sufferings.

Marc-André Cotton*

© M.A. Cotton – 03.2008 / regardconscient.net

*Marc-André Cotton, MA, the President of the International Psychohistorical Association, and an International Member of the Psychohistory Forum, is a teacher, independent scholar, and director of the French website Regard conscient, dedicated to exploring the unconscious motivations of human behavior. He authored the French psychohistorical book Au Nom du père, les années Bush et l’héritage de la violence éducative published in 2014 by L’Instant présent (Paris).

Notes :

[1] Denis de Rougemont, La Suisse ou l’histoire d’un peuple heureux, éd. L’Âge d’Homme, 1989, p. 13.

[2] Florence Noël and Élisabeth Eckert Dunning, « Les Suisses sont champions du stress au travail », Tribune de Genève, November 16, 2005.

[3]Salome von Greyerz and Elvira Keller-Guglielmetti, Le suicide et la prévention du suicide en Suisse, OFSP, 2005. Also read Suicide in the United States, Nation Institute of Mental Health.

[4] Le suicide et la prévention du suicide en Suisse, op. cit. p. 5.

[5] Guy Mettan, « Pour rendre vos enfants heureux demain n’hésitez pas à leur dire non ! », Tribune de Genève, November 5, 1995.

[6] Testimony of Marie Métrailler interviewed by Marie-Magdeleine Brumagne, La Poudre de sourire, éd. Du Rocher, 1982.

[7] Grégoire Turnsek, psychotherapist, cited by Alain Portner, « Maman j’veux que tu me paies un truc ! », Construire No 20, May 14, 1997.

[8] Alain Portner, ibid.

[9] In the Journal de la Société vaudoise d’utilité publique, No 9, septembre 1901, one can read: “Without any megalomania, it is true that domestic science, in the wider definition and most elevated sense of the word, is the foundation of any given society, instrument of well being, implement of hygiene, agent of concord and morality.” Cited by Geneviève Heller, « Propre en ordre » — Habitation et vie domestique 1850-1930 : l’exemple vaudois, éditions d’En-Bas, 1979, p.143.

[10] Augusta Moll-Weiss, Les écoles ménagères à l’étranger et en France, Paris, Rousseau, 1908, p. 49. In the early 1900s, education on domestic management was in Switzerland, as well as Belgium, “altogether the most official, the most complete and most popular” in Europe. Ibid., p. 17.

[11] Johanna Haarer, Die deutsche Mutter und ihr erstes Kind, Lehmann Verlag, München, 1940, p. 109.

[12] Johanna Haarer, Die Mutter und ihr erstes Kind, Carl Gerber Verlag, München, 1979, p. 100.

[13] Johanna Haarer, ibid., p. 123.

[14] Alain Portner, « Il est où, mon doudou ? », Construire No 48, November 26, 2002.

[15] Sabine Pirolt and Sonia Arnal, « Cet enfant qui tue le couple », L’Hebdo, November 11, 2004.

[16] Cited by Alain Portner, « Dur, dur d’être un p’tit dur », Construire No 5, January 28, 2003.

[17]) Alain Portner, ibid.

[18] Guy Mettan, « Pour bien éduquer vos enfants », Tribune de Genève, November 3, 1995.

[19] Le Temps, July 10, 2003. Article 126 of the Swiss Penal Code already abrogates the absolute right for parents to correct their children. Also read “Swiss court lets parents smack child”, Birmingham Post, July 10, 2003.

[20] Dominik Schöbi and Meinrad Perrez, Bestrafungsverhalten von Erziehungsberechtigten in der Schweiz, eine vergleichende Analyse des Bestrafungsverhaltens von Erziehungsberechtigten 1990 und 2004, Université de Fribourg, 2004.

[21] Philippe Barraud, « Ces bébés qui rendent fous », L’Hebdo, January 10, 2002.

[22] Quoted by Anne Lietti, « Le père, la mère, le bébé : l’épreuve à huis clos », Le Temps, January 12, 2002.

[23] Quoted by Ph. Barraud, op. cit.

[24] La violence psychologique Association romande des groupes d’accompagnement (AGAPA), case postale 138, CH-1752 Villars-sur-Glâne.

[25] Extracts from Bilan No 178, March 23, 2005. According to a recent survey, Bilan is read by one out of two business leaders in French-speaking Switzerland.

[26] Statistics of the Genevan Youth Health Service classify mistreatment of children into four categories : physical mistreatment, psychological mistreatment, sexual abuse and major neglect.

[27] Franz Schultheis and al., La maltraitance envers les enfants : entre consensus moral, fausses évidences et enjeux sociaux ignorés, analyse sociologique des transformations du rapport social à l’enfance dans le canton de Genève depuis 1990, Université de Genève, département ode sociologie, avril 2005, pp. 28-49.

[28] Art.11 of the Swiss Constitution states (Child and youth protection) : 1) Children are entitled to a specific protection of their integrity and support in their development. 2) They exert their rights themselves if they have the legal capacity.

[29] Motion No 1516 of 02/04/2003.

[30] Bulletin d’information du Département de l’Instruction Publique, April 19, 2004.

[31] Enfants en danger : activités du Service de la Santé et de la Jeunesse 2002-03, Genève, décembre 2003, reprinted by F. Schultheis, op. cit., pp. 188-196.

[32] Cécile Drouin, « Les enfants ne sont jamais trop petits pour les tâches ménagères », Le Courrier, May 25, 1992.

[33] Ibid., my emphasis added.

[34] Alain Portner, « Travail insuffisant », Construire No 6, February 4, 2003.

[35]) Sue Gerhardt, “Cradle of civilisation”, The Guardian, July 24, 2004. Sue Gerhardt is the author of Why Love Matters : How Affection Shapes a Baby’s Brain, Brunner-Routledge, 2004.

[36] Quoted by Michel Eggs, « La Suisse n’échappe pas aux critiques », Tribune de Genève, March 21, 2000.

[37] Daniel Audétat, « Albanais du Kosovo et d’ailleurs, pourquoi ils vont rester en Suisse », L’Hebdo, February 22, 2007.

[38] Survey conducted by Isopublic between December 14 to 17, 2005, on a representative sample of 1,005 residents of German and French-speaking Switzerland. (ATS, December 19, 2005)

[39] This public address followed the rape of a thirteen-year old girl, in Zurich, by several schoolmates of foreign origin or shortly naturalized. Christoph Blocher is quoted by Adrien Bron, « Le nouveau pavé anti-étrangers de Blocher : la punition collective », Tribune de Genève, November 28, 2006.

[40] Asked why his brother Christoph is so widely disliked, Gerhard Blocher answers : “It’s very clear : on any angle, [Christoph] is a successful rebel. It began in the family. At heart, we Swiss people like rebels. But when they succeed, they frighten us.” Gerhard Blocher interviewed by Andrea Vonlanthen, « Christoph weiss, dass Gott an ihn glaubt », Idea Schweiz No 45, November 7, 2007.

[41] Judith Giovanelli-Blocher, Das gefrorene Meer, éd. Pendo, 1999. Extracts of this untranslated book has been published by Le Temps, February 24, 1999, translation of Gilbert Musy.

[42] Alexandra Deruaz, « Chez Ems-Chemie, l’entrepreneur Christoph Blocher est très différent du politicien », Le Temps, October 23, 2003.

[43] D. S. Miéville, « L’UDC invite à se protéger des requérants comme du sida », Le Temps, August 14, 1999.

[44] Amnesty International, Révision de la loi sur l’asile, septembre 2006.

[45] Sylvie Arsever, « Le Comité de l’ONU contre la torture désavoue l’Office des migrations », Le Temps, November 29, 2007.

[46] Daniel S. Miéville, « La revanche du Parlement », Le Temps, December 13, 2007.

[47] René Knüsel interviewed by D.A. « L’UDC est menacée de scission », L’Hebdo, December 13, 2007.

[48] Excerpt from Christoph Blocher’s speech quoted by Le Temps, December 14, 2007.