Psychobiography

The Secret History of Alice Miller

by Marc-André Cotton*—Int. Psychohistorical Association

This article was published in Psychohistory News Vol. 40, No 2, Spring 2021

Abstract : An indefatigable advocate for children, Alice Miller passed away eleven years ago, leaving a legacy that raised awareness on issues such as childrearing violence, childhood traumas, and the roots of authoritarianism. But until her very end, she hid a dark secret that her son Martin eventually discovered. A recent documentary tracks his journey back toward truth. This article discusses the film and then presents and interview with the filmmaker.

This case was brought to public knowledge when Martin Miller disclosed, in a revealing book, that he had been psychologically annihilated by his mother’s unresponsiveness and his father’s violence—precisely the kind of bad parenting that the renowned psychotherapist and defender of children denounced in others in numerous publications. (For a review of Martin Miller’s book, see Marc-André Cotton, “Martin Miller’s Account of Alice Miller’s Childhood”, Clio’s Psyche, Vol 21, No 4, March 2015.) Considering Alice Miller’s international reputation, this unexpected disclosure raised fears that her son was unfairly settling scores and briefly fed her detractors’ arguments. But Martin also exhibited genuine self-awareness and shared precious biographical information about his mother’s own traumas. His revelations strengthen our comprehension of intergenerational transmission of traumas, particularly in wartime. Let us see how!

A cruel distancing

At the core of Martin’s inquiry lies his own feelings and lived experience as a child. Born in 1950, he was placed in the care of a nurse for a couple of weeks, then spent six months at cousin Irenka’s home. A few years later, when his trisomic sister was born, Martin stayed two years in a children’s home, deprived of all contact with his family. Throughout his childhood, domestic employees would function as parental substitutes. “My parents were strangers to me,” Martin confides in The True “Drama of the Gifted Child” (p. 119).

Fig. 1 : Alice and Andreas Miller around de 1950, in the frosty opulence of the Zurich bourgeoisie. (Le vrai « Drame de l’enfant doué », PUF, 2014)

Reading John Bowlby and getting acquainted with his attachment theory proved a painful wake-up call for Martin. He realized that his mother responded to his infant’s needs with a cruel distancing, as if the baby was dictating her own conduct—a position the young woman could not bear. Was this the reason Alice Miller showed no compassion as her son suffered daily violence from a humiliating and unpredictable father? Likewise, she did not intervene against her husband’s intrusive and compulsive toilet training of Martin. “You were always lying down in the room next door and yet were so far away from me,” Martin writes in one of his numerous letters to Alice (p. 125).

Fear of betrayal

After his mother’s death, Martin overcame his deep feelings of guilt and began to retrace the family history to understand “the wall of silence” with which his parents had surrounded themselves. What he then discovered from two cousins of Alice Miller in the United States shook up what he thought he knew about his mother. Born Alicija Englard to a Polish Jewish family, Alice only escaped the Holocaust by fleeing the Piotrków Trybunalski Ghetto—the first Nazi ghetto in occupied Europe—and adopting a Gentile family name to hide her real identity. Her father and paternal grandparents did not survive the liquidation of the ghetto in 1942, and she herself would always keep inside the excruciating fear of betrayal and subsequent deportation.

Alicija was the first born of a marriage that had been arranged by her grandfather Abraham Dov Englard, a Hassidic rabbi. Alice’s future father did not dare to disobey his own father when the rabbi imposed on him a cold and impassive wife. Many years later, what Martin learned about Alice’s grandparents and parents strangely reverberated with the frosty opulence of the Zurich bourgeoisie in which he grew up (fig. 1). “Arguments prevailed in the Miller household or, at the very least, an uncomfortable tension,” Martin writes about his own childhood home, adding that his mother projected onto his father Andrzej Miller—a Polish Catholic who turned out to be anti-Semitic—feelings of harassment that overwhelmed her during wartime, particularly in Warsaw where a blackmailer threatened to denounce her Jewish origin to the Nazi authorities (pp. 63-72).

Reversing the parent-child relationship

Alice Miller would reproach grown-up Martin for being like his father, whom he abhorred; Martin could not escape his mother’s projective identification of him as a persecutor. Evidently, Alice’s inability to be a nurturing mother stemmed from traumas that were firmly rooted in those years of Nazi persecution. “The more my mother labored to escape the agonizing ghosts of the war,” Martin came to conclude, “the more the past manifested itself as the living present.” (p. 140)

Martin is anguished by these intergenerational dynamics, common where families suffer severe trauma; he still pays a high price for his mother’s reenactments. To bear the daily torments of his or her inner wounds, the parent takes advantage of the child’s emotional support all the while giving the illusion of a reassuring closeness. This lures the child into a psychic maze that sometimes turns into a minefield that the child cannot escape. It is through these painful dynamics, Martin concludes, that the burden of trauma transfers to the next generation (fig. 2).

A moving search for truth

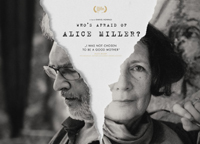

Swiss filmmaker Daniel Howald’s documentary “Who Is Afraid of Alice Miller” was nominated for the Solothurn Award in 2020. The film retraces Martin Miller’s journey on the tracks of his family history. It begins with the meeting, in the United States, of both protagonists: Martin Miller, who became a psychotherapist, and Irenka Taurek, his mother’s female cousin in whose house Alicija would take refuge when fleeing her own mother’s aggressions. In one of the first scenes, Martin confides to Irenka the deep resentment he still feels towards the tireless advocate of children for publicly condemning mistreatment that he himself was subjected to. “In this interview,” he shouts angrily about Alice Miller, “my mother describes exactly what she did to me and orders [others] not to do it! That’s my tragedy!”

In Berlin, Martin talks with Oliver Schubbe, Alice Miller’s therapist who corroborates the negative feelings that the mother projected onto her son. “These feelings were linked to her own experience of persecution,” he explains, “they had nothing to do with you, I can assure you!” But one remains speechless hearing the vengeful tone of some of the letters she wrote to her adult son. Martin and Irenka’s long haul continues in Warsaw and Lódz—where they pay a visit to the archives of the university Martin’s future parents attended in their youth—then Piotrków Trybunalski. One of the most powerful scenes of the film shows Irenka in the woods where she and Alicija were separated, as their families flee the advance of Nazi troops. As she was to be deported to Siberia, then Uzbekistan, Martin’s mother would get away by train, eventually reaching Warsaw.

Fig. 2 : For her entire life, Alice Miller would always keep inside the excruciating fear of betrayal and subsequent deportation. (Deportation of Jews of the Warsaw ghetto, April 1943, © Wikimedia Commons)

In the Polish capital, Martin discovers the apartment building where Alicija lived between age 18 and 22, among Germans, under the pseudonym of Alice Rostovska. There, his mother endured the intense persecution of szmalcownik—those Poles who blackmailed Jews by threatening to expose them—and suppressed a deep resentment she would later project onto her son. Martin briefly questions on the identity of a blackmailer who bore his father’s surname but fails to sort the truth out. The issue for second generation children, he suggests, is that they experienced their parents’ feelings through the process of transference, but with no clue about the reality of their traumas. He then concludes, addressing his late mother: “There always has been a wall between us, but I sense its shape more clearly. I better understand who you were. Piece by piece, another picture of you emerges.”

Marc-André Cotton*

© M.A. Cotton – 05.2021 / regardconscient.net

“Martin Miller was an indirect victim of the Holocaust!”

Swiss filmmaker Daniel Howald* was kind enough to answer our questions on his work, “Who Is Afraid of Alice Miller.” He argues that the damage caused by war in families goes on over generations.

Marc-André Cotton: How did your interest in the controversy about Alice Miller and her son Martin arise in the first place?

Daniel Howald: I had read Alice Miller’s books as a philosophy student. And one day, I heard an interview of her son on the Swiss radio. I didn’t know she had a son! I had become a filmmaker by then, and the next day, I sent Martin an e-mail asking what he would think of a documentary.

How did he react?

I wasn’t clear about the concept, so we met a few times over a one-year period. I didn’t want just a documentary for television and Martin was a bit skeptical, because he didn’t know how things would organize. We looked for a second protagonist and found Irenka Taurek, one of Alice Miller’s cousins in the US.

What was her contribution to this project?

Irenka turned out to be a very positive character, even fascinating by her charisma. As one can see in the film, her small size contrasts with Martin’s imposing stature, giving their relation a symbolic impact. She had stayed in touch with Alice Miller and knew her well because the two grew up together. Irenka had another perspective on her female cousin, who was not an easy person. She was also the first-hand source of the information Martin discloses in his book. We first met at her Californian home, then I invited her to make this trip to Poland with us. Despite difficulties, Irenka was willing to look into the past too. As she was ill, we had to postpone the shooting several times.

Would you say that Martin and Irenka both shared the same quest?

Martin was interested professionally as a therapist, but he also wanted to work on his own personal journey as a way of corroborating the healing path he shares with his clients. In spite of his personal struggles with Alice Miller, he is still convinced of the validity of her theories. Would you believe that Irenka herself was a psychotherapist of the Jungian school? I think they supported each other. Martin could probably not have taken this journey without her, nor Irenka without him.

Apparently, Alice Miller was a towering figure… and quite secretive too!

Indeed! Toward the end of her life, she began a therapy with Oliver Schubbe, a trauma specialist. He worked with her on the persecution she internalized from her wartime Warsaw period. Alice Miller allowed him to talk about it after her death. I contacted this therapist who also appears in my documentary. He told me that the fictional characters of Margot and Lilka, whom she presents in her sixth book Paths of Life, are actually two faces of herself. That’s the only glimpse of her past that she revealed publicly in her lifetime.

In your film, we see Martin doing research to find evidence for possible involvement of his father Andreij Miller with the Gestapo. Is there any basis to this, or is it one of his mother’s fantasies?

Well, we may never know the truth! We found indeed a namesake of Andreij Miller who worked for the Gestapo and was one of Alicija’s persecutors in Warsaw. She shared that information with her son, who suspected his father also hid a secret. Martin still believes so, but as a filmmaker, I cannot confirm it was the case. Was the persecutor his father or by some weird coincidence just someone with the same name?

From your point of view, what was the importance of this journey for Martin? Would you say that you were some kind of an enlightened witness for him?

It was not the purpose of this project. But yes, Martin came to certain conclusions. During this trip, he met other people who were children of Holocaust survivors. I think these conversations offered some peace of mind. He has a better view of what his mother endured, he told me, but the whole thing remains an emotional challenge. At the start of the film, he expresses anger that Alice publicly condemned mistreatment she herself inflicted on him.

What about the issue of trauma? Would you say that nowadays, we still minimize its effect on victims and their offspring?

What I tried to do is make visible a reality that, most of the time, remains hidden. I saw Martin’s suffering when I first met him. He is an indirect victim of the Holocaust, and his story and that of his famous mother are examples showing the Nazi period has not ended. It still pervades families. But we prefer to look the other way! Imagine the future of all these refugees, coming to Europe with war traumas, and who will also have children! This film is about a very topical issue.

And if Alice Miller had shared with her son the story of her tragic path of life, do you think it would have made a difference for him?

Definitely, but she could not do so! She had to protect herself from such experience in one way or another. That is precisely what she wrote in her books. But it might also be the reason why she had this urgent need to write, because she was a bright woman. In some of the two thousand letters Martin received from his mother that I could read, there are moments of grace when Alice understands what is at stake. Then, their dialogue turns back to conflict. But at least they were in relation, as opposed to his father who stayed a very mysterious person up to the end.

Interview by Marc-André Cotton

*Daniel Howald, MA was born in 1966 in Basel, Switzerland. Trained as a director and dramaturg for radio plays and documentaries at Swiss Radio DRS, while attending a two-year journalist training program at the Swiss Broadcasting Corporation (SRG SSR). He holds degrees (M.A.) in literature, philosophy and ethnology, and studied film for several years in Paris, Düsseldorf and Switzerland. Author and director of numerous television programs, radio plays and documentary films. Freelance director, dramaturg and scriptwriter since 1997. Member of the European Film Academy.

*Marc-André Cotton, MA, the President of the International Psychohistorical Association, and an International Member of the Psychohistory Forum, is a teacher, independent scholar, and director of the French website Regard conscient, dedicated to exploring the unconscious motivations of human behavior. He authored the French psychohistorical book Au Nom du père, les années Bush et l’héritage de la violence éducative published in 2014 by L’Instant présent (Paris).

Sources :

Miller Martin, The True “Drama of the Gifted Child”: The Phantom Alice Miller—The Real Person, 2018.

Howald Daniel, Who’s Afraid of Alice Miller?, Swissdok film, 2020.