Psychohistory

Religious violence: a paradoxical reality?

Abstract : The phenomenon worries even the highest authorities of the United Nations, which denounces an overflow of violence based on religion. The psychotraumatic dynamics leading to such extremes remain poorly understood. They are rooted in the denial of the natural sensitivity of children, subjected from birth on to the rigor of a doctrinal set of rules that diverts them from experiencing their true self.

The religious phenomenon is commonly associated with the search for transcendence, with the warmth of a community of faithful and with the respect of rites. The double etymology of the word religion, which derives from the Latin verbs relegere or religare, suggests that it fulfills a social as well as a sacred function: the first meaning referring rather to the practice of worship and the second to the subjective experience of the believer in relation to his or her god.

While religious beliefs bring tolerance, hope and brotherhood to most of their adherents, they are invoked by others to justify precisely the opposite, to the point that the United Nations recently proclaimed August 22 as the International Day of Remembrance for Victims of Violence Because of Their Religion or Belief. Concerned about a disturbing wave of intolerance and attacks on people of faith or places of worship, its Secretary-General, António Guterres of Portugal, said he wanted to oppose “those who misleadingly and maliciously invoke religion to create misconceptions, exacerbate divisions and spread fear and hatred[1]”.

Good and Evil

Of course, secular or even atheistic ideologies can also lead to terrifying violence. One thinks of the Nazi crimes, the Stalinist purges, wars legitimized by ethnicity or nationalism. But their “religious” dimension, both social and sacred, does not fail to surprise: exaltation of the feeling of belonging, veneration of rites, cult of personality... The designation of an “enemy” on whom to exercise such violence is another common feature of these belief systems.

In religion, the distinctions between Good and Evil, between the Pure and the Impure, are the result of circumlocutions that are often inaccessible to the community of believers, who leave it to a priestly elite to define the contours of these distinctions and are content to give credence to the doctrine that brings them together. The intimate conviction to bear evil is however widely shared by believers. It stems from a secular condemnation of their expressiveness as children, as they were subjected from birth on to the rigor of a doctrinal set of rules which diverted them from their true self. Like a parent towards whom the child directs an anxious eye to ensure that he is doing “the right thing”, the religious dignitary gathers his followers around the observance of rites, blames deviations and, in the most extreme cases, designates the heretics to the community’s vindictiveness.

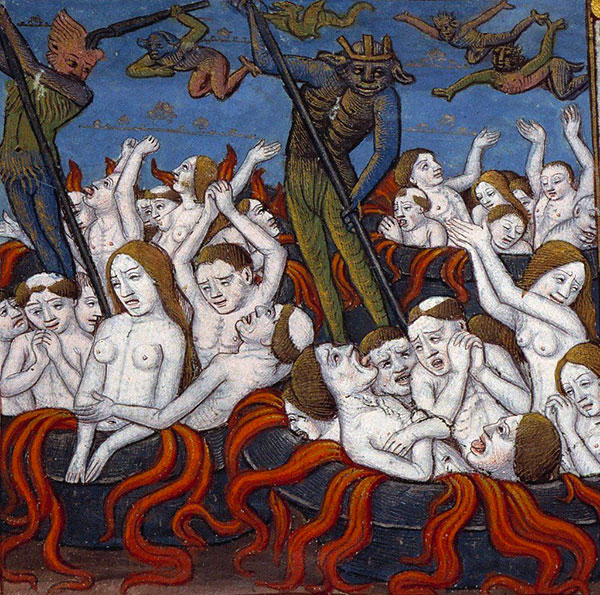

Fig. 1: The fear of hell has terrorized generations of children, leading them to experience themselves as born guilty (“Punishment of the lustful”, Compost and Shepherd's Calendar, Paris: Guy Marchant, 1493).

Original sin

As Guterres laments, the news regularly brings us back to this reality of religious violence being directed at selected targets outside a given congregation—“infidels” for instance. But it is also directed towards the inner group, against those who doubt the dogmas and are accused of apostasy or blasphemy. Women and especially children are traditionally the objects of such violence, suggesting that their vulnerability is a trigger in the reproduction of abuse and victimizing situations experienced earlier by their aggressors.

In Vingt siècles de maltraitance chrétienne des enfants (Twenty Centuries of Christian Child Abuse), Olivier Maurel has shown how the dogma of original sin, based on the belief in the evil in man, has left its mark on people’s minds and justified the worst abuses[2]. His book shows that over the centuries, a majority of children raised in Christianity have endured terrible punishments and that few theologians have escaped that fate. These tortures led them to see themselves as born guilty, to spread the creed of an original sin and the imperative need to purify their young flock by violence. To this day, sixty-two states have passed laws to abolish corporal punishment, yet we are far from recognizing in our children the manifestations of a spontaneous conscience and infinite sensitivity[3].

A denial of conscience

But then, where do our beliefs come from? All of them have been transmitted to us, often in an implicit way, but first of all by denial and violence. When in a movement of mood or anger, an adult turns against a child, the youngster is inflicted a terrifying rupture of a confirming relationship. When moreover the same adult asks him or her to suppress all emotion in the name of an education based on repression, he takes part in breaking the integrity of the child’s sensitivity which, little by little, withers and atrophies. It is from this first denial that our belief systems build up—the idea that our educators acted “for our own good” for example—and that the structures of our societies complexify.

This mechanism known as dissociation is now well studied. We understand that it is a neurobiological safeguard set up by the brain to survive intense stress. Suddenly covered with insults, the abused child no longer feels anything, she is disconnected and as if absent. But the emotional charge that she represses remains blocked in the amygdala of her brain and will resurface later, with the same stressful effects. Psychiatrist and psychotraumatologist, Muriel Salmona explains: “[The child] will have an inner voice that constantly insults her, and she will develop a poor image of herself, which will be the measure of what the family universe will have sent back to her throughout her childhood[4].”

Dissociative strategies

We can better understand how, on this basis, our belief systems and the veneration of rituals develop. Our traumatic memories are long-lasting and disturb both our cognitive abilities and our natural sensitivity. They contain, in an undifferentiated way, the violence and humiliations that were inflicted on us, their context and even the words spoken at the time, and last but not least the emotional charge imprisoned in the amygdala. Dr. Salmona specifies: “At the slightest link recalling the violence, [the traumatic memory] is likely to invade the psyche of the victim, and to make her relive all or part of what she has undergone, like an infernal time machine[5].”

To manage these emotional upsurges on a daily basis, the followers will develop a set of dissociative strategies ranging from avoidance behaviors, such as social withdrawal or submission to a hierarchical order, to anesthetizing practices, such as routine recourse to prayer or various rituals. Their adherence to the doctrinal corpus will be all the more necessary for their psychic survival that the denial of their being was deep and the violence brutal and repeated. Under the authority of their spiritual leader, the community of faithful will become the guarantor of a “normality” allowing them to spare their former abusers, their parents in the first place.

False Self and self-sacrifice

However, victims of abuse do not always react this way. In certain circumstances, for reasons that belong to their life history, they adopt dissociative behaviors involving the repetition of victimizing situations. In other words, they become abusers in turn and try to numb their traumatic memory at the expense of new victims.

Tolerated or even valued by the group in the name of a punitive and vengeful religiosity, these acts energize re-enactments that can go as far as murder. The self-hatred internalized in childhood is then brutally manifested by the total denial of the life of others, with a feeling of legitimacy provided by the exercise of dissociation.

Everyone will judge in which ways religious doctrines contribute to the structuring of what the British pediatrician and psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott already called the False Self[6]. Traditionally, the fear of punishment, the valorization of self-sacrifice through the cult of martyrs, the respect of beliefs to the detriment of reflection are part of the conditioning implemented to divert children from their natural impulses in the name of their adaptation to family and social practices. The consequences of these constraints on their psycho-affective development—a fortiori on their capacity to enjoy life together as adults—is rarely taken into account.

Marc-André Cotton

President of the International psychohistorical association (IPhA)

© M.A. Cotton – 2021.09 / regardconscient.net

Notes:

[1] “Religion-based violence: UN calls for messages of hate to be countered with messages of peace”, UN Info, August 22, 2019.

[2] Olivier Maurel, Vingt siècles de maltraitance chrétienne des enfants, Encretoile Editions, 2015. To my knowledge, there is not yet a similar critical work from other religious traditions.

[3] Only 13% of the world’s children currently live in a country that prohibits corporal punishment, which is not to say that in those areas it has disappeared, nor that other forms of routine abuse remain: humiliation, threats, blackmail, punishment or emotional neglect, for example. End Violence Against Children/End Corporal Punishment.

[4] For an excellent summary of her work, read Dr. Muriel Salmona, Châtiments corporels et violences éducatives, Dunod, 2016. The quote is on page 133.

[5] Ibid., p. 92.

[6] Donald W. Winnicott, “Ego Distortion in Terms of True and False Self” in The Maturational Process and the Facilitating Environment: Studies in the Theory of Emotional Development, International University Press, 1965, pp. 140-152.